Henderson and Others v Merrett Syndicates Ltd and Others

It has been suggested that their Lordships' attempt to explain the decision on Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd with reference to the principles in Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd was in danger of 'locking the front door but leaving open a rear window'. the intervening years have left the rear window is partially open'.

In Henderson and Others v Merrett Syndicates Ltd and Others, the House of Lords extracted from the case of Hedley Byrne & Co Ltd v Heller & Partners Ltd a broader principle.

The facts of the Henderson case concerned claims brought by Lloyds names against underwriting agents acting either as members agents or managing agents or both, in respect of huge losses suffered by the names as a result of negligent underwriting. The claims were brought both by names who were in direct contractual relationship with the underwriters and by names with whom the agents had no contractual relationship. The court held, inter alia:

- Where a person assumed responsibility to perform professional or quasi-professional services for another who relied on those services, the relationship between the parties was itself sufficient, without more, to give rise to a duty on the part of the person providing the services to exercise reasonable skill and care in doing so.

- An assumption of responsibility by a person or quasi-professional services coupled with a concomitant reliance by the person for whom the services were rendered could give rise to a tortious duty of care irrespective of whether there was a contractual relationship between the parties.

The leading judgment was given by Lord Goff who looked to the speeches of Lord Morris and Lord Devlin in Hedley Byrne for the principle upon which that decision was founded. In so doing, Lord Goff did not feel constrained by such concepts as the 'seeking and giving of information or advice nor 'the giving of information and advice by a person who is not under contractual or fiduciary obligation.’

For Lord Goff, and indeed the rest of their Lordships in Henderson, the fundamental importance of Hedley Byrne was to establish the following principle - an assumption of responsibility coupled with reliance by the claimant, which in all the circumstances made it appropriate that a remedy in law should be available. Furthermore, the assumption of responsibility could arise from a relationship between the parties that was either specific or general to the particular transaction and extended beyond the provision of information and advice to include the performance of other services.

Claims for purely economic loss can be pursued under Hedley Byrne. Lord Goff added that once a case was identified as falling within the principle of Hedley Byrne there was no need to satisfy the 'fair just and reasonable test' (applied to negligence cases generally by the House of Lords in Caparo Industries pic v Dickman).

Constraints to the broad principle enunciated by Lord Goff can be derived from the references to 'professional' or 'quasi-professional services'. Clearly that definition would include the acts of architects, engineers, surveyors and possibly contractors or sub-contractors undertaking a design function. Quaere whether it would extend to contractors or sub-contractors carrying out construction works as distinct from design. If Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd is followed where the common relationship in the construction industry of employer and nominated sub-contractor was considered to be a special relationship, the 'floodgates' would appear to open particularly if you consider the contractual structure in Henderson – the primary and sub-contractual relationship between the names the members agents and the managing agent. However, Lord Goff hinted at another potential restraint: the contractual chain. After distinguishing the situation arising in Henderson as 'most unusual' he went on to state:

'... that in many cases in which a contractual chain comparable to that in the present case is constructed it may well prove to be inconsistent with an assumption of responsibility which has the effect of so to speak, short-circuiting the contractual structure so put in place by the parties. It cannot therefore be inferred from the present case that other sub-agents will be held directly liable to the agents principal in tort. Let me take the analogy of the common case of an ordinary building contract, under which main contractors contract with the building owner for the construction of the relevant building, and the main contractor sub-contracts with sub-contractors or suppliers (often nominated by the building owner) for the performance of work or the supply of materials in accordance with standards and subject to terms established in the sub-contract. I put on one side cases in which the sub-contractor causes physical damage to property of the building owner, where the claim does not depend upon an assumption of responsibility by the sub-contractor to the building owner; though the sub-contractor may be protected from liability by a contractual exemption clause authorised by the building owner. But if the sub-contracted works or materials do not in the result conform to the required standard, it will not ordinarily be open to the building owner to sue the sub-contractor or supplier direct under the Hedley Byrne principle, claiming damages from him on the basis that he has been negligent in relation to the performance of his functions. For there is generally no assumption of responsibility by the sub-contractor or supplier direct to the building owner, the parties having so structured their relationship that it is inconsistent with any such assumption of responsibility. This was the conclusion of the Court of Appeal in Simaan General Contracting Co v Pilkington Glass Ltd.'

Of Junior Books, Lord Goff accepted that this case created 'some difficulty' to the above analysis; however he left it there, feeling that it was 'unnecessary ... to reconsider that decision for the purposes of the present appeal'.

The development of the law of negligence is continued in White v Jones.

[edit] Find out more

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

ECA Blueprint for Electrification

The 'mosaic of interconnected challenges' and how to deliver the UK’s Transition to Clean Power.

Grenfell Tower Principal Contractor Award notice

Tower repair and maintenance contractor announced as demolition contractor.

Passivhaus social homes benefit from heat pump service

Sixteen new homes designed and built to achieve Passivhaus constructed in Dumfries & Galloway.

CABE Publishes Results of 2025 Building Control Survey

Concern over lack of understanding of how roles have changed since the introduction of the BSA 2022.

British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951

A rich heritage of decorative and figurative sculpture. Book review.

A programme to tackle the lack of diversity.

Independent Building Control review panel

Five members of the newly established, Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended, panel appointed.

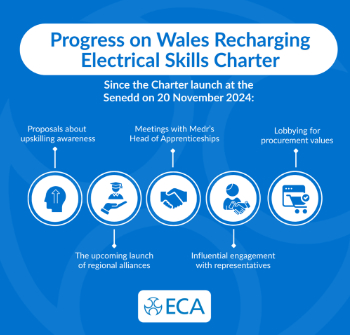

Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter progresses

ECA progressing on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.